Mechanical Bank

Period1889

Place MadeBuffalo, New York, U.S.A.

MediumPainted cast iron

Dimensions6 × 4 × 4 in. (15.2 × 10.2 × 10.2 cm)

ClassificationsToys & Games

Credit LineGift of Mr. Charles E. Hulit in Memory of Bessie Wilson Hulit, 1982

Object number1982.10

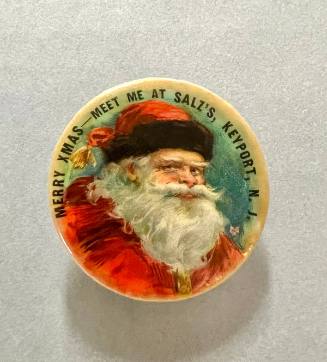

DescriptionA cast iron mechanical bank, depicting Santa Claus dressed in a peaked hood, fur trimmed tunic, and black boots, holding a sack in his right left hand. The figure's right arm is bent at the elbow, hand molded to fit a penny or similar coin. The Santa figure stands on a rectangular base just behind a chimney top, molded to appear as though made of bricks. "Santa Claus" is molded along the top of the base by the figure's boot tips. The entire bank is painted in enamel colors of red, white, and blue-gray. When a small spring tab on the base is pressed, the figure's right arm moves downward, dropping a coin into a slot at the top of the chimney. A small access panel, fastened with screws, can be removed from the underside of the bank to retrieve the coins.NotesThe Shepard Hardware Company was founded by John Davenport Shepard. Born on 14 June 1816 in Cobleskill, Schoharie County, New York, Shepard began work early in the steel and iron industry. At nineteen, he partnered with Edward Bissell to found J. D. Shepard & Company. In 1840, Shepard moved to Buffalo and began working with his older brother, Sidney Shepard (1814-1893). The company, Sidney Shepard & Co., produced tin and japanned items and novelties. In 1845, John married Clarissa M. Joy (1820-1895). The couple had four children: Anna (1845-1862), Charles G. (1850-1928), Walter (1853-1928), and Jesse (1861-1901). In that same year, John Shepard struck out on his own, founding Shepard Iron Works. In 1868, Shepard shut down that firm and went into partnership with Charles B. Clark, manufacturing hardware specialties. The company was short-lived, however, lasting only two years. In 1870 the partner dissolved the business into two separate firms, Clark Manufacturing Company and the Shepard Hardware Company. Brothers Charles and Walter joined their father in the family business, assuming control of Shepard Hardware Company at John Shepard's death in 1884. The firm was quite successful, and displayed its wares at a number of national fairs and expositions, including one at the Buffalo Fair Grounds in September of 1888. Local papers praised the company's products, noting that "the Shepard Hardware Company also made a display that attracted the attention of all, by the variety and excellence of the work exhibited." The firm produced toys, novelties, cooking items such as griddles, pans, and baking tins, specialty irons, and even ice cream makers. Charles Shepard held several patents, including one for a mechanical bank and another for an ice cream maker. According to an 1891 newspaper article, Shepard Hardware Company employed 360 males, 40 males under 18, and 23 males under 16. The company also emplyed 30 adult females, 18 females under 21, and 6 females under 16, most at work painting the finished products including fine detail work and decorative striping. Shepard Hardware Company seemed plagued by fires. On 14 April 1887, a fire was discovered on the roof of the factory but was quickly distinguished by local firemen. On 19 March, 1889, a "slight blaze" was put out by employees. Yet another fire, this one on 12 November 1892, was also put out before extensive damage occurred. Just a little more than a month later, an alert patrolman noticed a fire late in the evening of 23 December 1892. The blaze was put out by firemen, again "with slight damage." Around 7 p.m. on the evening of 9 May 1893, a fire began in the main factory building of the Shepard Hardware Company. Employees tried to put out the flames by using the building's own fire hose, but "for some reason it was of little use." The entire plant, covering almost six acres, burned in under an hour. Crowds gathered to watch as firemen attempted to quench the blaze. Newspapers described how the fire appeared to "burst out of the boiler room almost as if caused by an explosion." By the time firemen arrived on the scene, the flames were so hot that attempts to put out or even control the blaze were impossible. All the company's finished stock was destroyed, as were many of the patterns and most of the machinery. More than 400 Shepard employees were out of work. A week after the fire, Charles and Walter Shepard announced that they would pay each worker an additional six days' wages "as a partial consolation for the loss of work." The company's total losses amounted to well over $250,000. The company's extensive losses in the fire, coupled with the Panic of 1893 resulting in a widespread economic depression, spelled the end of the Shepard Hardware Company. By February of 1894, the company was actively selling off many of its patents. Many of its mechanical bank patents were purchased by the J. E. Stevens Company of Connecticut. After the closure of the firm, Charles Shepard continued in business, becoming a director of the Kensington Automobile Manufacturing Company of Buffalo and running a wholesale iron and coke business. Walter Shepard embraced politics, serving as city Treasurer, member of the Buffalo Republican Committee and the Buffalo Chamber of Commerce. In 1899 he ran in the Republican primary for mayor and lost, and in 1909 he was appointed city Assessor. The brothers died within three months of one another, Charles on 4 October 1928 and Walter on 15 December 1928. Many of Shepard Hardware Company's mechanical bank and toy novelty patents listed two inventors - Charles Shepard and fellow Buffalo resident Peter Adams. Peter Adams was born in France in 1843. His father and namesake Peter Adams, a tailor by trade, emigrated to Buffalo in 1847. Prior to the Civil War, son Peter was listed in city directories and in Federal and New York State Census records as a "cooper," or barrel maker. In 1861, Adams enlisted in Company K of the 100th New York Regiment and fought in the Civil War. After his discharge, he returned to Buffalo. He married Jane Stickney, and the couple had at least four children. For the rest of his career, Adams would work with metal, described in city directories and census records as a "moulder," "patternmaker," and as a factory foreman. He was also an active member of the local Post 254 G.A.R. in Buffalo. Adams was also creative, designing and fabricating the molds for his toy inventions for the Shepards. Over the span of a decade, from about 1882 to 1891, Peter Adams and Charles Shephard received at least five patents. It is unclear whether Adams worked as a paid employee for the Shepard brothers, or whether he worked as an outside consultant or specialist on a piece-by-piece basis.

Collections

Elizabeth Bowne

Unknown Artist

Sarah Hendrickson Van Schoick Reid

Chester Beach

Catherine L. Schanck

Unknown Artist

Ehrman Manufacturing Co.

Thomas Birch