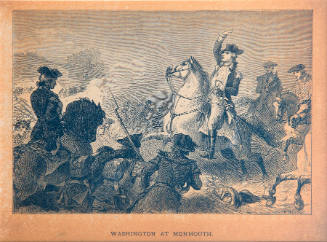

Washington Rallying the Troops at Monmouth

Artist

Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze

Period1857

MediumOil on canvas

Dimensions52 × 87 in. (132.1 × 221 cm)

SignedSigned lower right, "E. Leutze. / 1857."

ClassificationsLandscapes & Still Life

Credit LineGift of the Descendants of David Leavitt, 1937

Object number1029

DescriptionThis dramatic painting depicts an incident that occurred on 28 June 1778 near Freehold, Monmouth County. At the center of the crowded and animated work sits George Washington on a brown horse with sword upraised. General Charles Lee on a white horse appears to Washington's left. Immediately behind Washington is the Marquis de Lafayette with red uniform lapels, and behind him Alexander Hamilton with a white plume in his hat. Baron von Steuben appears at the extreme right edge of the composition wearing a metal helmet with a feathered plume. To the left behind and around General Lee is a large group of militia in a mix of informal clothing carrying muskets with bayonets. One of their number appears in the foreground attempting to get water from a small pool. To the right of the pool, a male holding a musket scoops water with his hat. Behind him to the right is a wounded soldier assisted by another militiaman. An artillery brigade is rushing to a hilltop in the distance behind Washington. The main American army in orderly ranks appears in the far distance in the extreme right hand corner of the canvas.The artist has included a depiction of Old Tennent Parsonage in the upper left distance. The blue sky is filled with the smoke of battle.Curatorial RemarksThe glorification of George Washington as a national icon reached its epitome in 1851, when the German-American artist, Emanuel Leutze, painted his famous canvas, Washington Crossing the Delaware (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), which portrayed the commander-in-chief as a triumphant hero. Two years later, the banker David Leavitt commissioned Leutze to create a companion piece, Washington Rallying the Troops at Monmouth (1854; University Art Museum at Berkeley), which shows the general taking charge of his disorganized army. In keeping with his exposure to the naturalism of the Düsseldorf School of history painting, Leutze sought to capture Washington’s state of mind by giving him a facial expression that reflected his anger at the turn of events. Although Leutze pictorialized one the most dramatic incidents of the American Revolution, his attempt to present a truthful portrayal of Washington’s emotions prompted negative remarks from a reviewer in The Crayon (10 January 1855), who felt that by showing the usually restrained general losing his temper, surrounded by his disarrayed troops, was indecorous. It was, he said, “not in the slightest degree heroic, and not calculated . . . to elevate the character of its hero in the minds of his countrymen.” While the penman for The Crayon misread the painting, Leavitt understood that it was intended to evoke Washington’s leadership skills as he corrected the mayhem that surrounded him. He subsequently commissioned the artist to produce a smaller copy for his daughter, Elizabeth, in 1857. That version, now in the Association's collection, replicates the Berkeley picture with one exception: aware of the controversy surrounding the original, Leutze replaced the scowl on Washington’s face with a placid, almost spiritual, countenance that seems strangely out of place in view of the turmoil surrounding him. Leutze’s Battle of Monmouth paintings synthesize the real and the ideal. He presents an accurate rendering of the men’s uniforms and weapons and his likeness of Washington is a faithful one (although the general was still riding a white horse at this time). Leutze’s portraits of the Marquis de Lafayette and Alexander Hamilton (in the black hat) on the right are correct too, but neither officer was actually by his side at this point in the battle. Leutze’s interest in capturing the psychology of the main figures comes across most effectively in his portrayal of General Lee, slouched on his horse on the left: his posture conveys the dejection he surely felt after being reprimanded by his superior. However, Leutze took liberties with Lee’s appearance, depicting him as a heavy-set man when he was actually thin and scrawny. Recent scholarly research on the Battle of Monmouth has revealed that the confrontation between Washington and Lee did not occur as depicted in Leutze's painting. NotesIn the spring of 1778, Sir Henry Clinton, Britain’s commander-in-chief for the American campaign, was informed that a fleet of French ships was on its way to aid the Continental Army. On 18 June, fearing that his forces would be trapped in Philadelphia if the mouth of the Delaware River was blockaded by the French navy, he decided to march about 10,000 British and Hessian soldiers overland to New York City (a Loyalist stronghold), a route that took them across Delaware and into New Jersey. The following day, General Washington and his troops left their encampment at Doylestown, Pennsylvania, and proceeded stalk the British. While stationed at Manalapan Bridge on the morning of 28 June, he sent an advance force of about 5,600 patriots, under the leadership of Major General Charles Lee, to attack the British rearguard as they left Monmouth Courthouse for Middletown. Upon being alerted that the Americans were on his trail, Clinton and several of his finest regiments remained behind and, led by Charles Cornwallis, they conducted a surprise attack against the Continental Army’s right flank. After receiving conflicting reports about the exact whereabouts of his foes, concerned about his supply of ammunition, and unable to communicate with his soldiers, Lee ordered a general retreat that caused panic and bedlam among his troops. While advancing from the west with 8,500 men of his own, Washington was notified that the colonists were moving back across the Rhea Farm. Infuriated, he immediately rode to the scene and after intercepting Lee, he quickly brought his disorganized Yankees under control; as the Marquis de Lafayette later remarked, “His presence stopped the retreat . . . his fine appearance on horseback, his calm courage roused by the animation produced by the vexation of the morning, gave him the air best calculated to excite enthusiasm.” After regrouping shortly after noon, the rebels established a strong defensive position along the Perrine Ridge and a bloody and exhausting battle ensued until about 5 o’clock, when the British pulled back. Having stood their ground against the enemy, Washington and his men spent the night on the battlefield, while the Redcoats set up camp to the east of the Rhea farm, remaining there until escaping (unbeknownst to the Americans) around midnight. The largest land artillery battle of the Revolution had come to an end.

Collections

Felix O. C. Darley

Unknown Artist

Unknown Artist

John R. Chapin

Felix O. C. Darley

John Rogers

Unknown Artist

Dennis Malone Carter

John Chester Buttre

Unknown Artist

Thomas Birch

Unknown Artist